Archiving a Wrestler: Photograph, Orality and the Tactile

The memory of a physical culturist—particularly of one who practices kusti (wrestling) or similar dialogic forms—is not easy to preserve after their passing. Interviews, photographs and even audio-visual footage can help piece together only a partial memory of their art, the essence of which lies in the elusive tactility of their physical presence, training and techniques. The closest approximation to the core of their practice can perhaps be traced in their pupils, who carry forward their legacy as embodied archives.

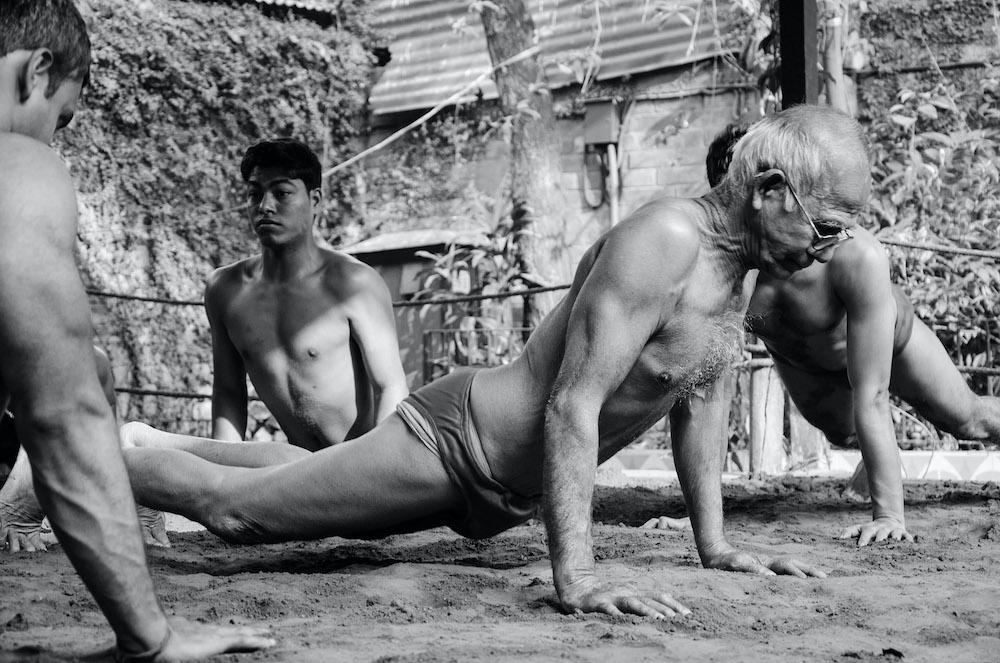

Around 2013, as a part of the University Grants Commission-funded project Physical Cultures of Bengal conducted by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University; Prof. Abhijit Gupta, Deeptanil Ray and Nikhilesh Bhattacharya had the privilege of getting to know Biswanath Datta (1929–2020). At the time, he was the only living pupil of the legendary wrestler, Jatindra Charan “Gobar” Goho. The eighty-four-year-old was still visiting his old akhara on Goabagan Street in north Kolkata on a regular basis, going through his regime of warm up exercises and supervising the training of younger practitioners.

Biswanath Datta and his pupils at Gobar Goho's Gymnasium. (Photograph by Kawshik Ananda Kirtania.)

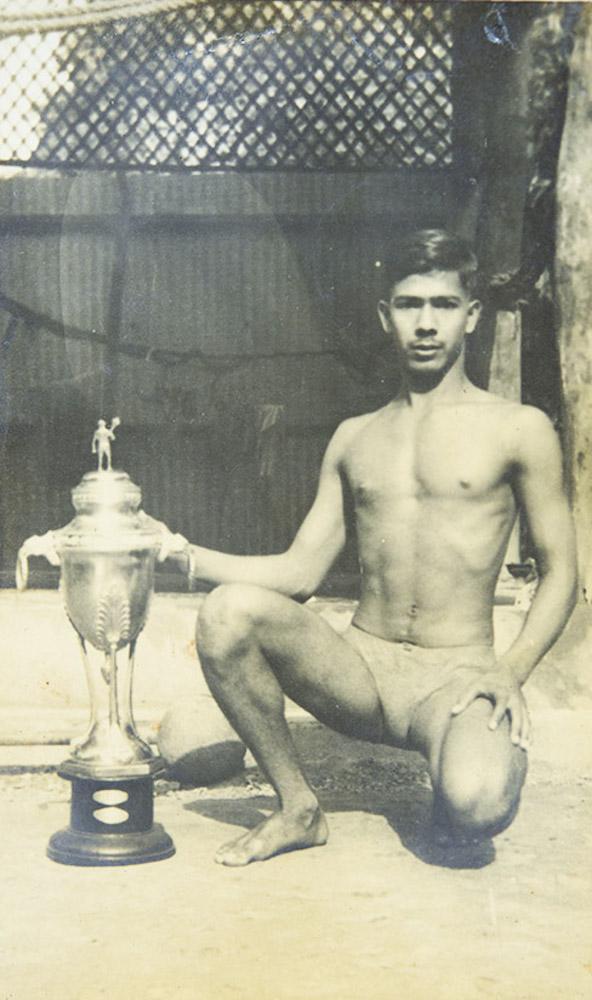

Young Biswanath Datta at Gobar Goho's Gymnasium. (From Biswanath Datta's archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

For a man who had accomplished much in his own time at the national level, Datta was surprisingly self-effacing. He had vivid memories of his teacher—their first encounter, the support he received during family crises and even the exact bend of the index finger, which indicated the number of push-ups they would have to do—much of which he transmitted to his own pupils. For us, as documentarians and oral archivists, Datta had stories from his long and colourful life. He had even curated a Gobar Goho museum in one of the large rooms that surrounded the central courtyard (the wrestling ring), preserving a few pieces of equipment. He also showed us a folder that contained a photograph album, newspaper clippings, loose negatives and a few stray journals.

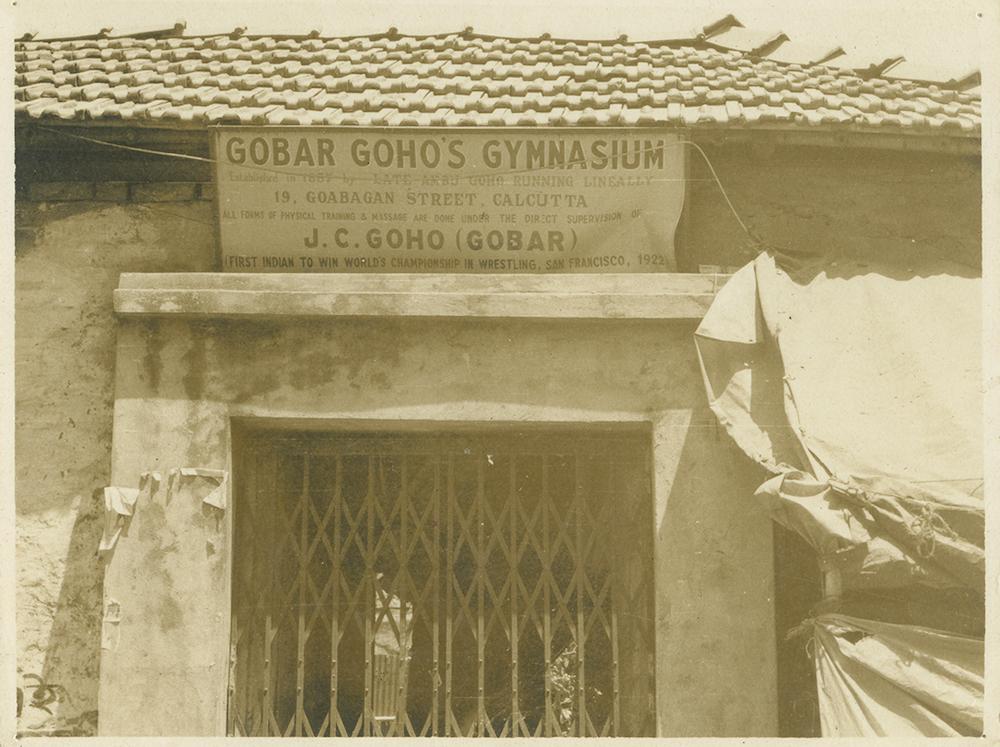

Entrance to Gobar Goho's Gymnasium. (From Biswanath Datta's archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

The photograph album was, essentially, a documentation of the life and times at the akhara. A photograph of the entrance—which remains largely unchanged—indicates that it was established in 1887 by Ambu Charan Goho, and that training continues under the direct supervision of Gobar Goho, “First Indian to Win World’s Championship in Wrestling, San Francisco, 1922” (a claim that has been qualified recently by Rudraneil Sengupta).

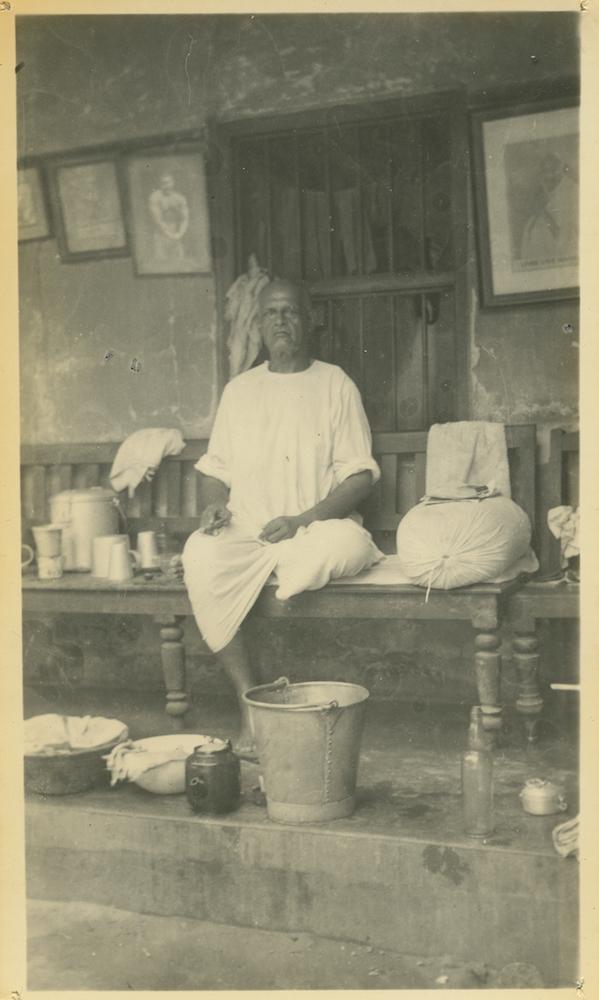

Gobar Goho in his gymnasium at an advanced age. (From Biswanath Datta's archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

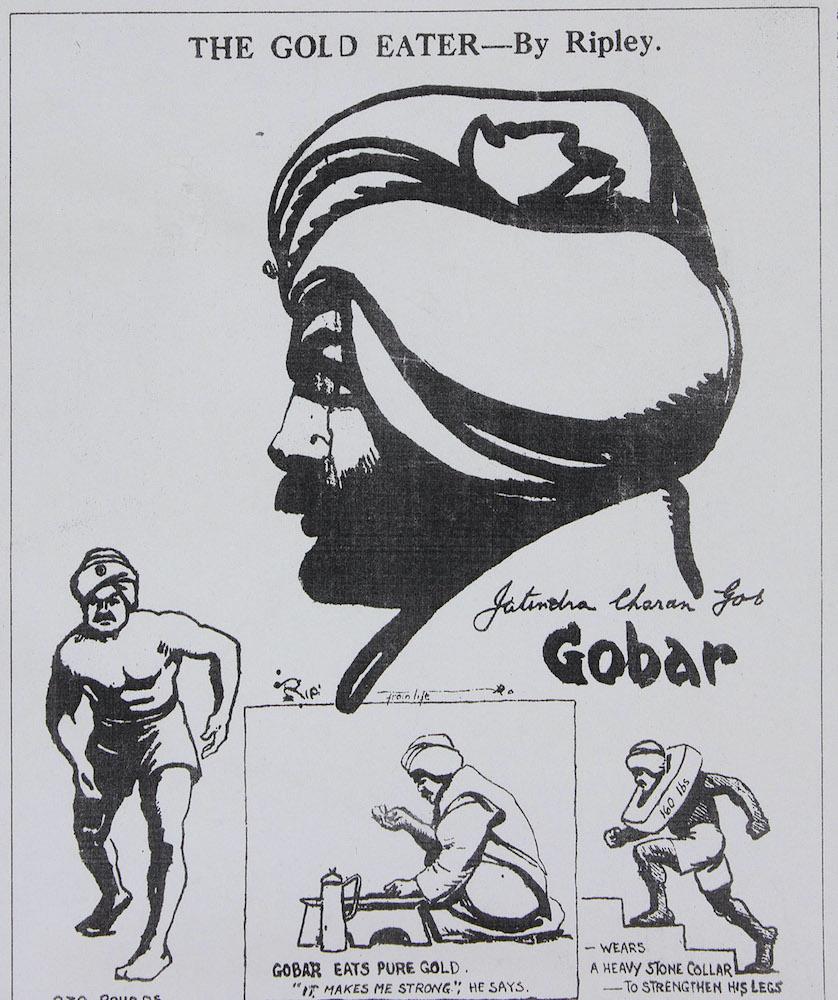

"The Gold Eater," featured by Ripley, in The Globe and Commercial Advertiser. (New York, 21 January 1921. From Biswanath Datta archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

The teacher himself appears at an advanced age in another photograph, seated on a wooden bench and equipped austerely with some basic utensils and pillows. Above his head, hang a few framed photographs of body-builders and wrestlers along with a portrait of M.K. Gandhi. This persona is a far cry from Goho’s self-fashioning on North American soil, where he was featured in oriental regalia on Ripley’s column as an Indian who eats pure gold to become strong. As an admirer of G.B. Shaw and Oscar Wilde, and critic of Charlie Chaplin; he was hailed, rather patronisingly, as a rare exception among wrestlers for possessing both brains and brawn.

There are multiple gharanas of wrestling in the subcontinent. These have parallel—though dissimilar—trajectories of negotiating colonial and postcolonial modernity, while trying to transition to the new professionalism in international sport. Unfortunately, recent historiography has largely focused on the Hindu Bengali traditions, with the exceptions of Sengupta and Joseph Alter—who study the Benares gharana more closely. Some of the loose photographs suggest that while Goho’s akhara may have pursued one tradition, they were in touch with developments in other parts of the subcontinent.

Collectible photograph of anonymous wrestler. (From Biswanath Datta's archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

Collectible photograph of anonymous wrestler. (From Biswanath Datta's archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

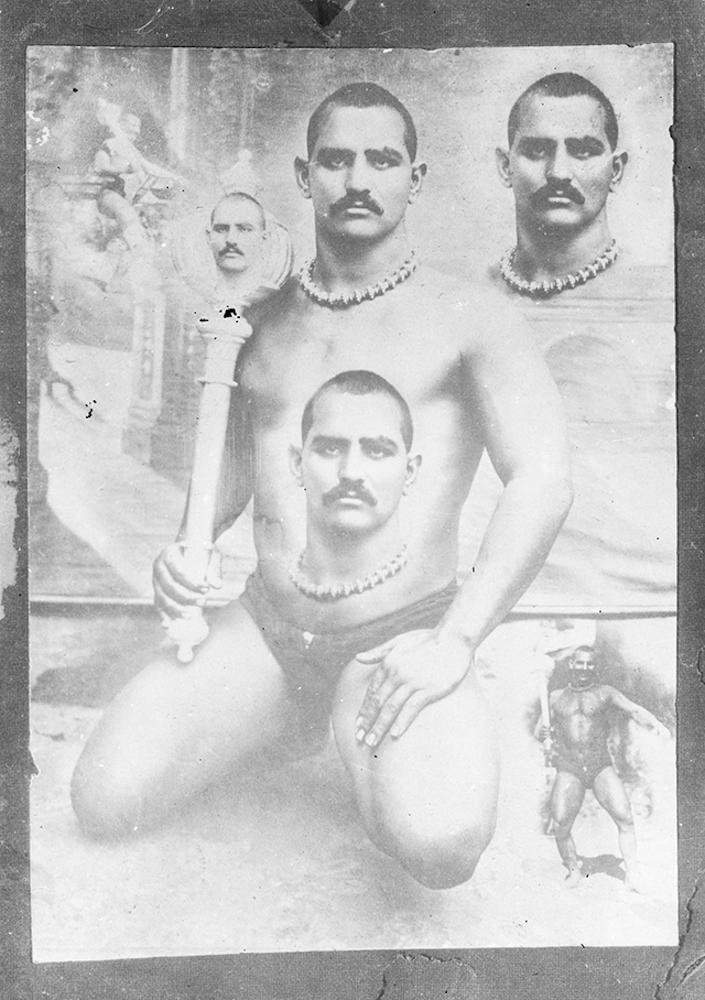

Datta’s archive contains a curious set of six images that appear to be photographs of greeting cards featuring star wrestlers. Three of these show busts or full-length figures of anonymous wrestlers, with a fourth placed in a more elaborate setting: surrounded by potted plants and a chair. Perhaps the most intriguing one from a technological point of view, features a man striking a Hanuman-like pose—a distinct departure from the Greco-Roman classicism of body-builders—with a number of images of his head superimposed on and around him.

Collectible photograph of anonymous wrestler. (From Biswanath Datta's archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

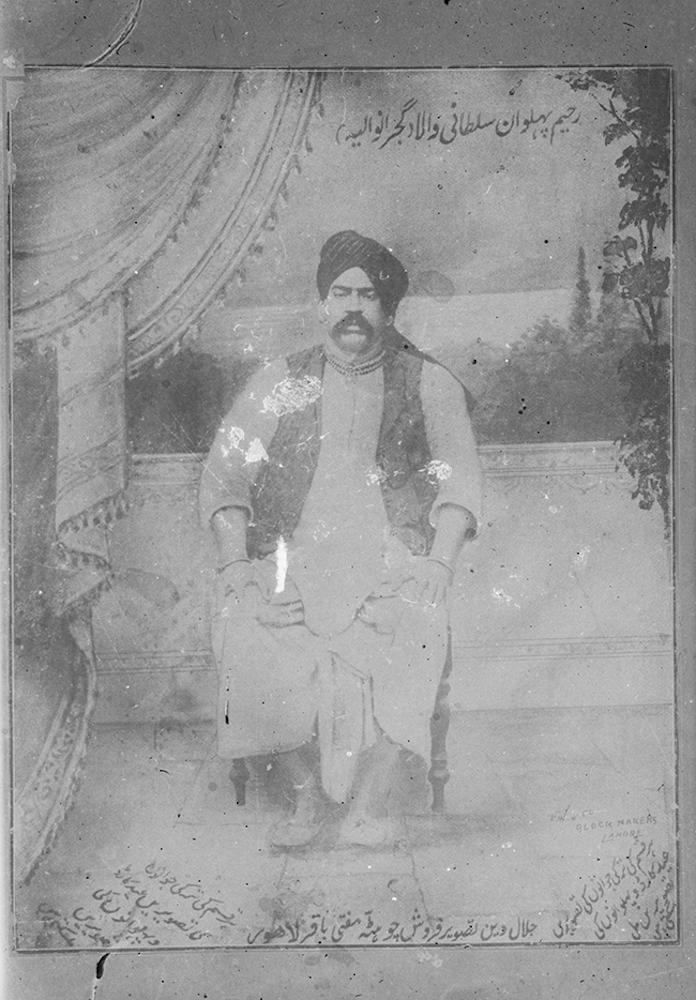

Collectible photograph of Rahim Pehlwan Sultaniwala. (From Biswanath Datta's archive. Digitised by the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University.)

The only one that helps us situate these cards is of the legendary Rahim Pehlwan Sultaniwala (Gujranwala), whose might was equalled occasionally only by the Great Gama himself. Printed and sold at Jalal-ud-din Tasvir Firosh in Lahore, the card advertises: “Har kissam ki turki jawano ki tasvire ki card aur pehlwano ki tasvire mil sakti hai (You can find cards and photographs of wrestlers and youthful men of all descriptions)." Although documentary evidence is unlikely to surface, it is worth speculating if, like the images of Eugen Sandow and other body-builders, these photographs and cards too could have lent themselves to a homoerotic gaze.

In case you missed the first part of this series on body-building and masculinity, you can read it here.

All archival photographs are courtesy of the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University. I would like to thank Ehtesham Hassan and Brinda Dasgupta for their help with the Urdu reference.